Belarus’s presidential election: an appetite for change

On 14 July, Belarus’s Central Election Commission refused to let two popular challengers to Belarusian president Aliaksandr Lukashenka register for the country’s forthcoming presidential election. After that decision, a kilometre-long queue formed in Minsk as people waited to submit complaints to the commission, and protesters gathered in other cities. Meanwhile, a united campaign in support of the presidential candidate Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya is gaining public momentum across the country.

New survey data gathered by ZOiS in the run-up to the election demonstrate the popularity of presidential challengers among young people in Belarus. In particular, three electoral campaigns have invigorated public interest in politics. All three alternative candidates have been supported by an impressive degree of public mobilisation, large numbers of signatures for their candidacies, and solidarity events across the country.

First, Viktar Babaryka, a former head of the bank Belgazprombank, emerged as the main challenger to the incumbent. After being arrested on 18 June, he continued his campaign from prison but on 14 July was not allowed to register as a candidate. Another challenger was Valery Tsapkala, who started his diplomatic career as an ambassador to the US and in 2005 set up the Belarus Hi-Tech Park. He promised to create an entrepreneurial future for all of Belarus, but too many of the signatures on his application to become a presidential candidate were declared invalid.

Third, Siarhei Tsikhanouski, a prominent vlogger, was barred early on from registering. He was later arrested and remains in prison. His wife, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, ran instead and is now a registered candidate. After the decision on 14 July, she was joined by Maria Kalesnikava and Veranika Tsapkala, representatives of the two other excluded candidates. The female trio has emerged as the most momentous challenge to the Belarusian president in the last twenty-six years.

The president’s popularity: a sensitive matter

Presidential elections in Belarus are usually legitimising rituals for the country’s autocratic leadership. Since 1994, Lukashenka has won every contest with more than 70 per cent of the vote. In this election campaign, state media have said on many occasions that the president enjoys an approval rating of more than 60 per cent. However, public opinion data collected by the National Academy of Sciences of Belarus indicate that only 24 per cent of citizens in Minsk trust the president.

Online polls of Belarusians’ backing for various presidential candidates led to the meme Sasha 3%, which mocked Lukashenka’s declining support. These polls were met with a blunt response from the government, which threatened to take action against independent media that conduct online polls on the election.

It remains notoriously challenging to gain insights into the country’s political mood. Yet, ZOiS conducted an online survey among urban youth to enquire into their political views. From 22 June to 4 July 2020, we surveyed 2,000 Belarusians aged 18–34 living in the country’s six largest cities. The data show young people’s rising political interest over recent months, their active participation in protests, and their desire to end Lukashenka’s presidency.

Young voters on the street

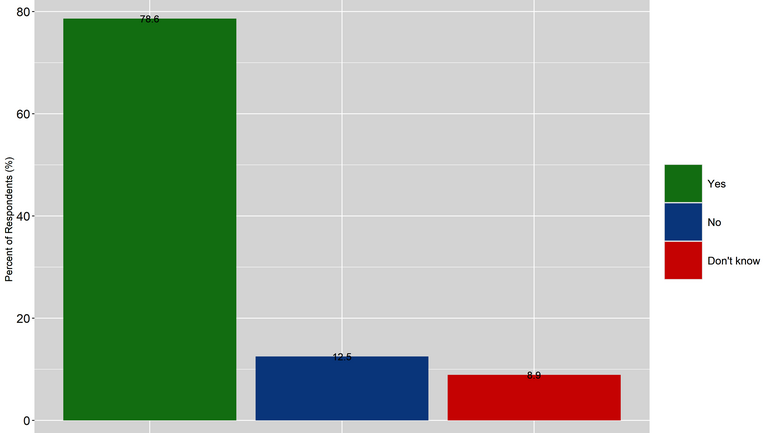

Among the respondents, nearly 80 per cent said they intended to participate in the presidential election (figure 1). The general level of political interest was also high, with 60 per cent indicating that they were interested in politics. However, young people’s political enthusiasm stirred a harsh response from the Belarusian government even before the official start of the election campaign. Arrests of political activists, journalists, political bloggers, and protesters signalled to the population that the ruling elite would respond to opposition with repression.

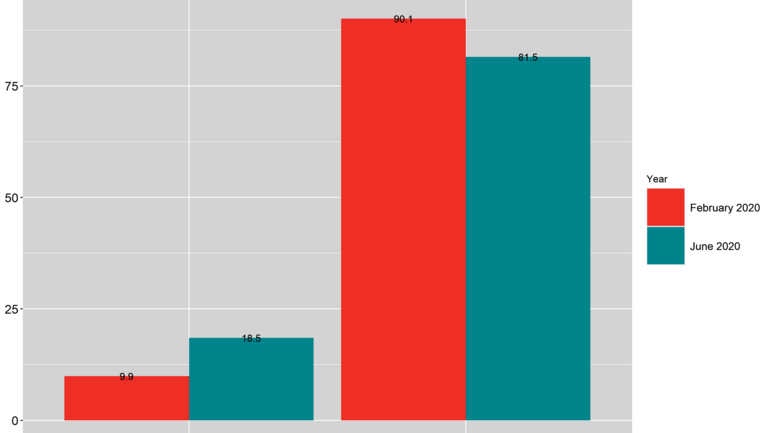

When we asked young Belarusians which candidate they would vote for, nearly 10 per cent stated that they would opt for the incumbent (figure 2). Babaryka was the most popular candidate, chosen by more than 45 per cent of respondents, followed by Tsapkala, with almost 13 per cent. Since the survey was conducted, supporters of these two candidates—and, potentially, some who said they did not know who to vote for—may conceivably have moved to support Tsikhanouskaya.

More than 60 per cent of those who chose an opposition candidate said that their preferred candidate represented their political opinions. Only about 10 per cent of Tsapkala’s supporters and 15 per cent of Babaryka’s said they would vote for that candidate because they disapproved of the incumbent. Less than 10 per cent of respondents answered that there was no appealing alternative to Lukashenka.

Support for the opposition was highest among younger respondents, those who are more interested in politics, and those who live in the capital. However, support for an opposition candidate did not relate to respondents’ occupations, incomes, levels of education, or levels of self-declared religiosity. In other words, the opposition attracts a socially diverse spectrum of supporters.

Backing for the incumbent was highest among older respondents, those with lower political interest, and those more likely to declare themselves religious. Disposable income also correlated positively with support for Lukashenka.

Since the two most popular candidates were barred from running in the presidential race, young people have been left to get involved politically outside the electoral arena. Recent weeks have seen one of the most remarkable political mobilisations in the country’s history. In our survey, nearly 20 per cent of respondents said they knew people who had participated in protests over the last year (figure 3). Younger respondents were more likely to say they knew protesters, which ties in with youngsters being more prepared to take personal risks. In particular, young people who live in Minsk were more likely to know protesters, but political activism is clearly not limited to the capital.

Not just a rite of passage

Elections in stable autocracies can turn into moments of political mobilisation, even when the electoral outcome seems obvious. Whether the current degree of mobilisation in Belarus can be maintained beyond the present window of opportunity remains to be seen. It is conceivable that Lukashenka’s re-election combined with harsh repression will bring new challenges to this stable autocracy. Whether and when institutional change will result from what seems like a broken social contract is uncertain, although it is clear that Belarus has entered uncharted waters, irrespective of the result of this year’s presidential election.

Félix Krawatzek is a political scientist and senior researcher at ZOiS, where he works on projects studying historical memory, memory laws, and youth. He also coordinates the ZOiS research cluster Youth in Eastern Europe. Maryia Rohava is a researcher at the University of Oslo, where she focuses on politics in Belarus and Russia.