Poland’s viral election

Amid Poland’s Covid-19 lockdown, heated political confrontations persist over whether the presidential election will take place as scheduled on 10 May. In the run-up to the planned vote, ZOiS conducted a survey among young Poles to shed light on their fractured political views. A sizeable share of Polish youth supports the government’s conservative values. But others have mobilised against its social policies and its curtailing of the judiciary’s independence—albeit without a centre of gravity.

The potential opportunities of a crisis

Crises provide opportunities to get things done that previously seemed out of reach. Choices made in a crisis often affect society or politics for a long time. Worldwide, Covid-19 pandemic presents such a crisis, in which Poland needs to decide how to proceed with the upcoming presidential election.

Jarosław Kaczyński, the leader of the ruling conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party, has so far succeeded with his crisis manoeuvres. In early April, a change in Poland’s electoral law introduced postal voting, effectively turning the post office into the electoral commission. As soon as the law had been approved in the lower house of the Polish parliament, the country’s deputy defence minister, Tomasz Zdzikot, became head of the post office. On 5 May, the senate, which is controlled by the opposition, rejected the introduction of postal voting. The postal election therefore lacks a legal basis.

Poland’s leadership portrays itself as having reacted to the pandemic with determination. The resulting restrictions largely prevent campaigning and have demobilised the opposition. It is unclear what kind of political message might be appealing to voters right now. The Polish government took the pandemic as an opportunity to further restrict political freedoms on the ground of protecting public health. At the same time, support for the current president Andrzej Duda remains high, and he is portrayed positively on PiS-dominated television. But recent polls have also shown that PiS is losing support to the opposition Polish People’s Party.

But the pandemic and the public mood might evolve quickly, especially if doubts spread about the official number of cases of the coronavirus disease, Covid-19. The timing of the election is therefore crucial. Under current legislation, a vote in person is scheduled for Sunday, which, however, seems unfeasible. But if the election is delayed for long, the diverse opposition might consolidate its campaigns while the disastrous economic consequences of the pandemic become apparent. Kaczyński himself argued that Poland needs to focus on fighting the economic crisis: ‘People always blame the authorities under such circumstances.’

Resistance to holding the election in May also comes from within the ruling class, notably from prime minister Mateusz Morawiecki and health minister Łukasz Szumowski. Deputy prime minister Jarosław Gowin resigned over the controversy and is leading the challenge against postal voting as head of the Agreement party, an electoral ally of PiS.

Young Poles and the election

In recent elections, support for far-right parties among young Poles has made headlines. Yet, young people have also mobilised against controversial PiS policies, such as a bill to further tighten Poland’s strict abortion law.

ZOiS conducted an online survey among young people to find out more about their political attitudes and voting intentions in the presidential election. From 18 to 31 March 2020, we surveyed 2,000 Poles aged 16–34 living in cities and towns with more than 100,000 inhabitants. Among the respondents of voting age, two-thirds intended to participate in the election; the remaining third were either undecided (19 per cent) or did not want to vote (15 per cent).

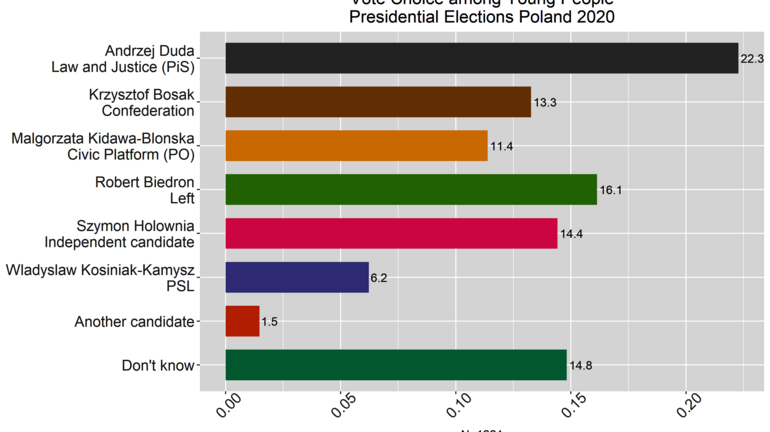

The largest share of young people, in particular those living in Warsaw, said they would vote for the incumbent in the first round of the two-round contest (see figure 1). The preferences of the remaining respondents were split across the opposition. Robert Biedroń, a progressive and openly gay candidate; Szymon Hołownia, a Catholic TV celebrity; Krzysztof Bosak, a young far-right Eurosceptic who campaigns for Poland’s exit from the EU; and the centre-right Civic Platform’s Małgorzata Kidawa-Błońska all attracted between 11 and 16 per cent of the vote in the survey.

Compared with the general population, young people express significantly less support for Duda. Rather, their political preferences spread across the country’s wide political field. Polish youth prefer candidates with clear, outspoken messages—be they progressive or conservative.

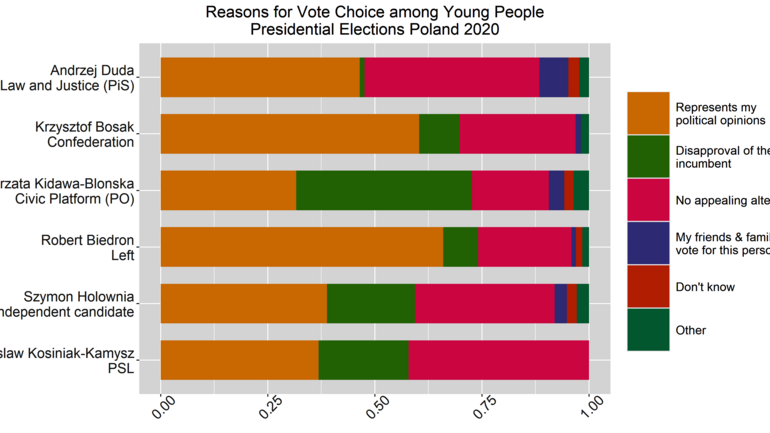

What motivates young people’s voting intentions? In Poland’s fractured political landscape, young people showed a certain conviction for Biedroń and Bosak (see figure 2). By contrast, preference for Kidawa-Błońska was motivated by disapproval of the incumbent or a perceived lack of alternatives. Only some 30 per cent of respondents said they would vote for her because she represents their political opinions. Reasons to vote for Duda were split between approval of his political beliefs and a perceived lack of alternatives.

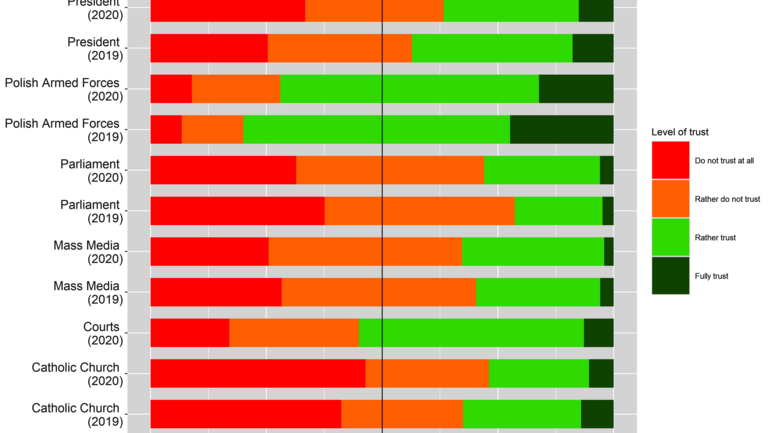

The election is taking place in a context of low political trust. Most Polish institutions have had poor overall trust values for at least two years. The media, the Catholic Church, and the parliament are trusted the least, whereas the president is seen in a slightly less negative light (see figure 3). But the polarisation of Poland’s politics and the erosion of democratic standards seem to have left a clear imprint on how people think about institutions.

Four days before the election is due, it remains unclear whether the vote will take place. Numerous scenarios for postponing the election are possible. It seems increasingly likely that the government declares a state of emergency to postpone the ballot until August and then holds a presidential and an early parliamentary election simultaneously. But it could also change the constitution to extend Duda’s term by another two years. Whatever the outcome, recent weeks have shown the political and social opportunities of this unpredictable crisis. Poland’s erosion of democratic standards might nevertheless backfire on the ruling class in weeks to come, creating the greatest political crisis in Poland since 1989.

Félix Krawatzek is a political scientist and senior researcher at ZOiS.