Russian history and realities in 2017

Among the newly elected members of the German Bundestag who have a so-called migration background (i.e. they or at least one of their parents are not German citizens by birth) are two Russian Germans—ethnic Germans from the Soviet Union and its successor states. Both were born in Kazakhstan and came to Germany in the mid-1990s. Both belong to the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and are the only members of parliament with a Russian German background. This fact was emphasised by the AfD representatives, especially through Russian-language channels, and interpreted to mean that AfD is the only party representing Russian Germans in the parliament.

German mass media discussed the connections between the Russian Germans and the AfD long before the election, in the context of anticipated Russian interference in the German election and politics. In the area of public communication, this threat was anticipated as the manipulation of online discussions and public opinions by Russian trolls or bots, and as the consumption of Russian state media by former Soviet, now German, citizens. Under the influence of Russian TV, which translates nightmare stories about Europe being flooded by foreigners, these alienated citizens, many worried, would vote for the AfD.

The scenario of cyberthreats has barely come to be realised, but the two ethnic German resettlers from the former Soviet Union are now members of the new populist right-wing party in the Bundestag. Has the AfD become the party for Russian Germans? This question is easier to handle if we differentiate between its two aspects: Has this party received an above-average percentage of votes from Russian Germans? And does the party represent them in particular?

Preferences and voting behaviour

Exit polls do not collect data on the backgrounds of voters, so we have only limited opportunities for empirically grounded judgments on the voting behaviour of Russian Germans. An indirect indicator is the extensive voter migration from the Christian Democrats to the AfD. The long-standing preference of ethnic German resettlers (Spätaussiedler) for the Christian Democrats deteriorated during recent years, to the benefit of other parties.

This follows the path of political differentiation pioneered by other migrant groups—especially Turks, who however initially favoured the Social Democrats. According to a 2016 study by the Expert Council of German Foundations on Integration and Migration, resettlers’ preference for the AfD was almost 5 per cent in 2015, or three times higher than among voters without a migration background. Therefore, it is plausible that a substantial number of former Christian Democrat voters among the resettlers did not deviate from the overall trend and voted for the AfD.

Another, more direct way to get evidence on the voting behaviour of Russian Germans and other post-Soviet migrants is to analyse the results in their segregated residential areas. Such areas developed due to the state policy of allocating place-of-residence to the new resettlers and their individual choices. At regional elections 2016 and 2017, the AfD achieved double-digit (at some points, extremely high) results in several such residential areas, and the federal election confirmed the trend. To take one example from Baden-Württemberg: in the city of Pforzheim, which is considered an AfD stronghold, the party received 25 per cent of the vote, and its candidate (not a resettler) won a direct mandate with the same percentage of votes. In the district of Haidach-Buckenberg, where Russian Germans are the majority, the AfD received about 43 per cent. In the Bundestag election, the party and its direct candidate, a Russian German, won only about 20 per cent (a 37 per cent in Haidach-Buckenberg were watered down by the poorer results from other voting areas in Pforzheim).

However, we should not extrapolate the trends from segregated residential areas to post-Soviet migrants or Russian Germans in general (and a great majority of voters with post-Soviet migration background are resettlers and their family members). It is not clear how big the share of such residentially segregated voters is among all voters with a post-Soviet background. A simple extrapolation would be even less convincing due to the correlation between the residential choices and belonging to a certain sociocultural milieu.

Much symbolism, few Russian German specifics

The second question is whether the AfD represents Russian Germans in a particular way. As a young party, the AfD provides better chances to new party activists, including Russian Germans. To get a good position on the party list at Bundestag elections, an activist has to have become active years ago with the party’s youth organisation. The newcomer party provides better opportunities for lateral entries, but it does not express a particular affinity to Russian Germans.

Both Russian German members of the Bundestag were elected via the AfD party list, in Thuringia and in Lower Saxony. Anton Friesen, an active member of the Young Alternative and a researcher for the AfD in the Thuringia regional parliament, was put on a party list without seeking a direct mandate. In Lower Saxony, Waldemar Herdt sought a direct mandate in the constituency Osnabrück-Land. In this constituency, he and his party received only about 7 per cent of the vote; he entered the Bundestag not due to the support of some local Russian German networks, but rather because of a good position on the party list. Several members of the interest groups of Russian Germans in the AfD who had been active during the electoral campaign did not enter the parliament. The support of the party could not be converted into a promising position on the party lists.

During the latest electoral campaign, the AfD again addressed Russian Germans in the Russian language or through bilingual materials and events; and some printed materials were translated by party activists. This bilingual approach is less a practical need than a symbolic gesture, which pays respect to Russian Germans as a special group. The materials themselves, however, did not focus on the issues specific to the resettlers, such as recalculation of their pensions. The central issues of migration and asylum policy, internal security, and sanctions against Russia were much more present. In the AfD-related discussion groups on the Russian social networking site vk.com, the topics of Islam, asylum, and migrants are much more prominent than those directly related to the situation of Russian Germans.

Relations between Russian German activists, other citizens with this migration background, and party structures are too complex to be reduced to the AfD being the party of or for Russian Germans. Many parties look to gain the support of the Russian Germans, but the AfD claims to have it already.

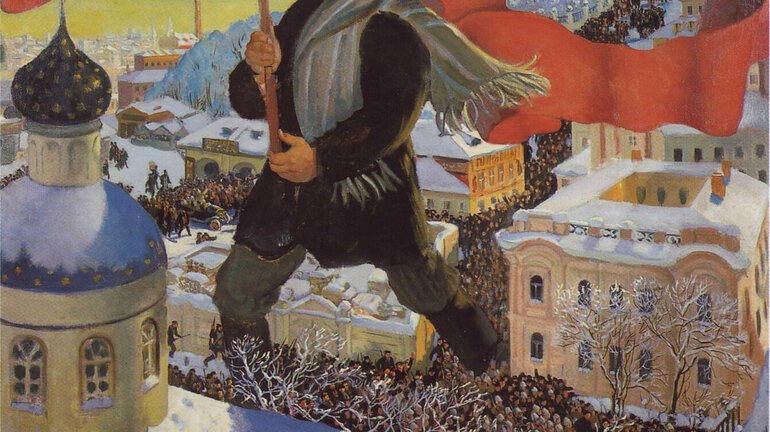

Historian Jan C. Behrends is reasearch associate at the Centre for Contemporary History and teaches at the Humboldt Universität zu Berlin. His research focuses on the modern history of Eastern Europe with an emphasis on modern dictatorship, urban history and violence. In February 2017, he co-edited the volume „100 Jahre Roter Oktober. Zur Weltgeschichte der Russischen Revolution“.