A “quite recent” event? Young Poles’ awareness of history

At a ceremony in the Polish city of Wieluń, German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier asked for Poland's forgiveness 80 years after the start of the Second World War. He spoke in Polish as well as German in a country where debates about remembrance of the Second World War are emotionally charged. In recent years, these controversies around Poland’s history have increasingly centred on the history policy narrative propagated by the current nationalist-conservative government, such as the debate about the concept of the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk, which has now prompted four Polish historians to bring legal action against the Museum’s new director.

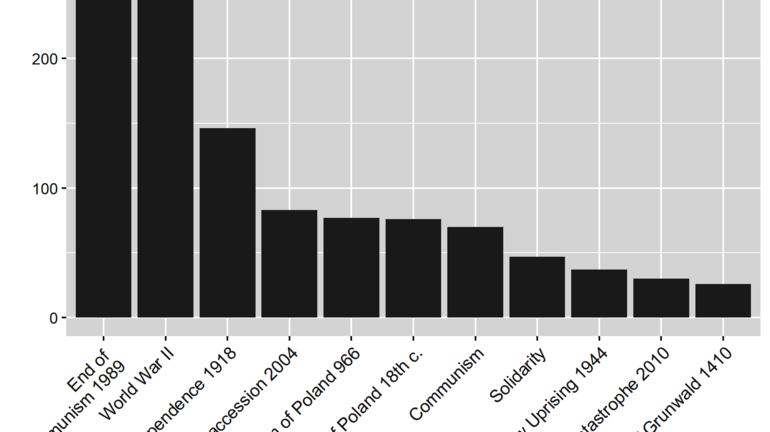

An online survey conducted by ZOiS in February 2019 provided some revealing insights into young Poles’ awareness of history. Around 2,000 Poles aged between 16 and 34 were asked to name the historical event of greatest importance in understanding Poland today and what they associated with this event. In top spot was the collapse of communism in 1989 (mentioned by around 14 per cent of respondents), closely followed by the Second World War, with Polish independence in 1918 in third place and EU accession in 2004 in fourth.

The collapse of communism

The collapse of communism is viewed in predominantly positive terms. Almost one in three respondents associate it with the attainment of democracy and freedom of opinion in Poland. The regaining of independence in 1918 was mentioned by around a quarter of respondents, with roughly the same number referring to economic aspects such as alignment with Western living standards.

“A political transformation which allowed us to form an independent government, grant citizens more freedom and liberalise the economy.”

The Round Table Talks between representatives of the communist Polish United Workers’ Party and opposition groups in 1989, which opened the way for radical political change, have mainly negative associations. Some respondents associate these talks with a lack of decommunisation and the failure to prosecute communists, resulting in their continuing influence to this day. Politicians, mainly from the ruling conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party, have been arguing for years that former communist elites have too much of a say in present-day Poland. Several other respondents criticise what they regard as the continued influence of politicians from the Round Table era, which they believe has worsened divisions within the country. However, it is clear that the majority of today’s young Poles associate the collapse of communism with positive social and, indeed, economic development.

The Second World War

Since the fall of the communist regime, a wide-ranging public debate about the Second World War has begun in Poland and numerous museums have opened. Lately, however, the main line of conflict has been drawn between the national-conservative policies on history propounded by the government, which is keen to establish state control over the process of remembrance, and those who oppose it. The key motifs of this national-conservative narrative are a special emphasis on the heroism of the Polish nation, Polish victimhood and Polish efforts to save the Jews. These seemingly slight shifts in official policy towards the past negate historical complexity and open the way for controversies with other states.

Almost 14 per cent of respondents see the Second World War as the seminal historical event, with almost as many ranking it in second place. According to one respondent, the Second World War is a “quite recent” event in Polish history. Several other respondents explicitly state that its effects on Polish society can still be felt today.

“This was a traumatic experience for Poles. History is passed down from generation to generation and the Polish people are still living in the past […].”

There are various reasons for this: on the one hand, the untold numbers of dead and innocent victims, according to one in four respondents, who specifically mention Poles, Jews and the intelligentsia. On the other hand, one in five respondents also refer to the destruction of the country, the need for it to be rebuilt and the resulting slower pace of economic development. And while many young Poles see the economic impacts of the Second World War as extremely significant for present-day Poland, this does not signify support for the Polish Government’s demands since 2017 for war reparations from Germany.

Connotations of heroism such as the collective strength of the Polish people, the selfless dedication of the fighters and the emergence of the nation are mentioned by around 12 per cent. Here, there are traces of the – albeit not widespread – national-conservative narrative, evident also in the traits associated with the Warsaw Uprising: resilience, courage and the essential character of the Polish nation. This counter-narrative to the customary focus on Polish martyrdom, i.e. the conventional understanding of Polish history as mainly one of victimhood, is also evident in works published by the state-run Institute for National Remembrance in recent years.

Detailed knowledge of history

Some respondents mention historical events much further back in the past, such as Poland’s conversion to Christianity in 966. Around 4 per cent see this as the seminal event – almost the same number as for EU accession. Many see it as marking the start of Poland’s emergence as a nation and emphasise that Poland is a Catholic country, although a few criticise the considerable influence still exerted by the Church. The Partitions of Poland in the 18th century, which continued until the re-emergence of the independent Polish state in 1918, are associated by many with the country’s current economic and social division into “Poland A and B”, in other words, the distinction between the western and the eastern part of the country.

All in all, the findings attest less to nostalgia than to a well-developed awareness of history among young Poles, who spot numerous associations with the fall of communism and the Second World War in particular and relate them to the present day. Elements of national-conservative history policy barely resonate. The question that remains, however, is to what extent these narratives are internalised by the young Poles who are directly targeted by education policy, public campaigns, multimedia museums and so forth. The parliamentary elections this October will show whether Poland’s right-wing conservative government, in office since 2015, will imprint its view of history more deeply on young Poles in future.

[1] Out of 2,002 persons surveyed, 1,321 answered the question on the key event in Polish history.

Nadja Sieffert is studying East European Studies with Political Sociology at the Institute for East European Studies, Freie Universität Berlin. She is a research assistant at ZOiS.