Crimea: the interface between politics and culture

Five years have passed since the start of the Crimea crisis – a by-product of Euromaidan and the ousting of the then President Viktor Yanukovych – and the referendum on the status of the peninsula, staged by the government of Crimea with the backing of Russian special units. The majority of the local population of this Black Sea peninsula voted in favour of its integration into the Russian Federation. Crimea had been part of the Russian Empire from 1783 but was transferred to the Ukrainian SSR in 1954. After 1991, it belonged to independent Ukraine, albeit with autonomous status.

But how has this latest turn of events impacted on Crimea’s cultural scene? On the face of it, the effect does not seem to be particularly dramatic, but nor has it triggered a cultural resurgence, although this would have been desirable as a contribution to the political debate. As before, the peninsula has three official languages – Russian, Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar. As before, cultural professionals who are unhappy with the status quo are leaving, while those who find Crimea fascinating are staying put.

After the devastation wreaked by wars and disasters in previous centuries – the Russo-Turkish War (1768-1774), the Crimean War (1853-1856), German occupation during the First and Second World Wars, the deportation of the Crimean Tatars and the desolate situation after 1990 – geopolitics once again has the peninsula in its grip and existential issues have pushed cultural life into the background. On top of this is isolation – an outcome of the Ukrainian government’s neglect.

Geopoetics instead of geopolitics?

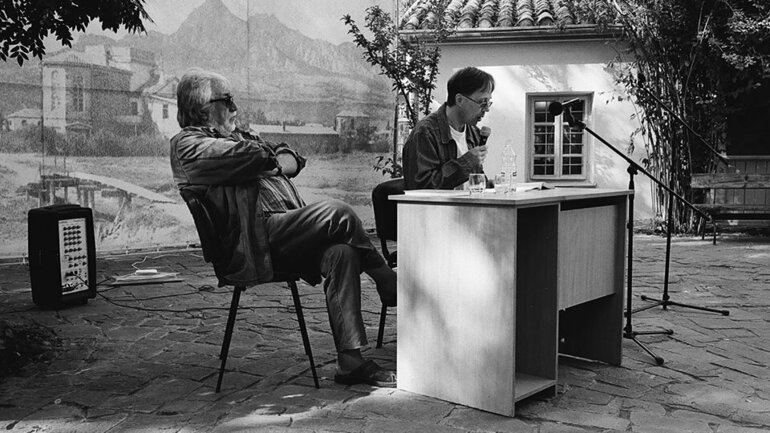

The Russian-Ukrainian poet, publisher and organiser Igor Sidorenko (Sid), himself from Crimea, has developed the concept of “geopoetics” as a counterpoint to the tensions since the 1990s. It is intended to divert attention away from ominous and exhausting geopolitics and focus instead on humanistic ideas. Since 1993, Sid’s “Crimea geopolitic club” has held regular meetings of the Bosphorus Forum, a dialogue platform for the peninsula’s artistic community and cultural professionals from all the sides that are at odds over its future – Russia, Ukraine and the Crimean Tatars. From the outset, this experimental forum – a blend of arts festival and conference – has made space for collaborative conceptual actions, including land art, in which works of art are created outdoors out of natural materials, and happenings, a form of action art in which artists improvise events and encourage the public to take part.

The participants, all Russian speakers, include Ismet Sheikh-Zade, a Crimean Tatar artist and descent of a sheikh, whose family were deported to Uzbekistan; the Buryat poet Amarsana Ulzytuyev; philologist Alexander Korablev from Donetsk, who has remained at his university post despite the conflict raging around him; poet and poetry researcher Natalya Azarova, who divides her time between Moscow and Alupka; Jewish translator and dramatist Jan Shapiro; and Andrei Polyakov, one of the best-known poets writing in the Russian language. Polyakov himself acknowledges that his work revolves around Crimea and its literary life, and that this is central to his being. Polyakov is the human embodiment of geopoetics: existence, as he sees it, is intertext, while the writing self is a semiotic body, and meaning is symbolic, dynamic and ever-changing.

Although the concept is a good fit for the participants, the Forum, originally scheduled to take place every two years, has been held ever more infrequently of late due to lack of funds. Participants pay their own travel costs. The September 2015 Forum focused on the role of translation as a creative cultural phenomenon. The lectures, readings and book presentations were required to comply with specific organisational criteria set by the Moscow Institute for Literary Translation, without whose support the event could not have taken place. Sid had previously managed to identify private sponsors to cover some of the costs, including a guesthouse in Kerch which provided accommodation for festival participants. Western partners would be very welcome but are conspicuous by their absence.

Despite the challenges, the peninsula is by no means a cultural desert. More than 700 events per year – social, environmental and, in a narrower sense, cultural – are listed on the trilingual Culture Ministry’s calendar, including Crimean Tatar and Jewish festivals, memorial events for the victims of deportation (although in 2014, the Crimean Tatars were requested to shift these commemorations out of the city centre to the outskirts of Simferopol, even though Crimea’s largest mosque has been built in the centre of town), First and Second World War remembrance, and literary events, notably the Gumilev Festival and the Voloshin Festival in Koktebel.

The latter takes place every autumn, with the costs again borne by the participants, some of whom are noted liberals. Attendees in 2018 included Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty correspondent Tatyana Voltskaya. In Koktebel, Maximilian Voloshin’s House of a Poet is a literary ark for international guests, as befits a house shaped like a ship. Natalya Miroshnichenko – previously a Maidan supporter – has been the centre’s Director for more than 10 years. The House of a Poet is Crimea in microcosm, inspiring and providing space for those who live by creativity. The festival continues this tradition, despite intermittent power outages.

Crimea as text

But this is also a region which has Russian writers and artists to thank for much of its familiarity. Russian artist Ivan Aivazovsky’s paintings convey the beauty of the seascape, while Alexander Pushkin’s immortalisation of the Bakhchysarai Foundation saved the Khan’s Palace from later destruction by the Soviets. Pushkin also despatched his eponymous anti-hero Eugene Onegin to the Black Sea to cure his dandified St. Petersburg ways. Leo Tolstoy wrote about the horrors of the Crimean War in his reports from battle, while Anton Chekhov sent his Lady with the Little Dog out strolling along the promenade in Yalta and created a garden adjacent to his house for public enjoyment. Like so many other sites in the locality, they have become inspirational places – much like Crimea itself.

True, the peninsula’s cultural development is prone to stall when money from Moscow fails to reach its destination, as with the 1.6 billion roubles approved in 2015. Nevertheless, Crimea seems to have symbolic weight within Russian and European culture that generates a momentum all of its own. German-language writers are among those who have looked to – and around – Crimea for inspiration in recent years, sometimes with the same ambivalence that characterises politics. While Esther Kinsky focuses on the cold on the peninsula and announced a personal boycott after its annexation by Russia, Olga Martynova followed her “keen curiosity” and paid a visit to Crimea straight afterwards. [1]

Now is the time for an international geopoetics forum about Crimea, in the form of a dialogic platform for academic and creative analysis of the crisis as a starting point for long-term peace-making.

[1] Esther Kinsky and Martin Chalmers: Karadag Oktober 13: Aufzeichnungen von der kalten Krim. Reisebericht, Berlin 2015; Olga Martynova: “Der goldene Apfel der Zwietracht. Krim-Tagebuch 2017”, in: Über die Dummheit der Stunde. Essays, Frankfurt a. M. 2018, 241-292.

Tatjana Hofmann is a Literary Studies researcher at the Slavic Seminar, University of Zurich. Her research interests include Russian and Ukrainian literature of the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries, as well as travel literature, autobiographical works and the linkages between literature, ethnology and other media.