Young Russians agree with official World War II narrative, but criticize excessive victory celebrations

Victory Day celebrations are a central component of Russian memory politics. This year’s 9th may parade on the occasion of the 75th anniversary is probably going to be postponed due to the Corona-Crisis. A new ZOiS Report provides insights into the attitudes of young people towards the celebrations. The study reveals that while the Soviet victory in World War II still provides a shared historical foundation for young Russians, many young people also criticize today’s victory celebrations as excessive and would prefer a more intimate remembering.

Under Russian president Vladimir Putin, historical narratives have become a central component of the Kremlin’s attempts to shape the identities of Russians at home and abroad. In the report, the authors examine what World War II means for young Russians and how the conflict is represented for them, notably in literature and film: ‘While a one-sided interpretation of World War II is central for Russian patriotic education and history textbooks, more critical historical narratives are encountered in literature. Newer state-subsidised films tend to repeat Soviet ideas about the war and build on emotions’, Slavicist Nina Frieß and political scientist Félix Krawatzek summarise.

In accordance with the official narrative, young people’s perceptions of World War II centre on heroic victory and Soviet strength, downplaying violence and victimhood, aspects which are present in literary and filmic war narratives.

United against the external threat

A common theme in cultural artefacts, political discourse and young people’s perceptions of World War II is the trope of national and social unity. ‘Russian youth yearn for social cohesion, which many associate with the Soviet era. The unity of the diverse people of the Soviet Union in a war against a common enemy contrasts with today’s geopolitical situation’, the authors of the study observe.

A crucial historical anniversary

However, frustration with today’s commemorations cut across political views. ‘There is widespread agreement on the need to transmit memory from one generation to another, but many prefer a more personalised way of remembering. There was a broadly shared view that today’s celebrations are inappropriate: they were described as “for show”, too dramatised, and detached from the population’, describes Félix Krawatzek.

Stalin as a controversial figure

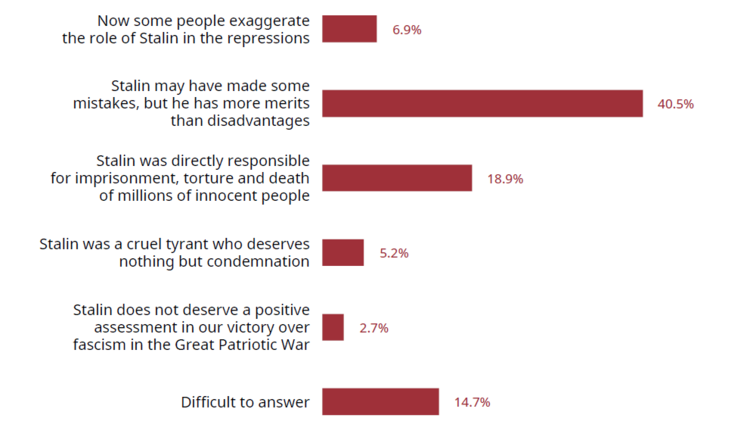

Survey respondents hardly mentioned Stalin or the violence of Stalinism when referring to World War II. This view matches Russia’s teaching practices, emphasis on military heroism, and political discourse with its focus on economic development after the war. (Fig.1) ‘Views on Stalin and the violence that civilians were exposed to are particularly contested. Although young people are generally aware of Stalinist repression, evaluations of that period of history differ sharply among young Russians today. Information in literature, exhibitions, and films about violence are publicly available but reach young people only to a limited extent’, Nina Frieß concludes.

The analysis is based on two sets of sources. The first is a series of online surveys among young people living in Russia’s major urban areas, alongside focus group interviews. The second is a canon of popular historical literature and films aimed also at young people. ZOiS conducted the cross-sectional online surveys among young people aged 16 – 34 in April 2018 and 2019. The focus groups took place in Yekaterinburg and St Petersburg in June 2019.

Figure 1: Young Russian's view on Stalin