Big Election Sunday in Central Asia Does Not Bode Well for Democracy

10 January 2021 was voting day in Central Asia, with a presidential election in Kyrgyzstan and parliamentary elections in Kazakhstan. On the face of it, they were unrelated events: these two countries may be neighbours, but they differ considerably when it comes to politics. However, a closer look reveals similarities that give little cause for optimism.

All going to plan in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan is governed by an authoritarian regime. Veteran President Nursultan Nazarbayev may have stepped down in March 2019, but he retains his firm grip on the reins of power. So far, his hand-picked successor Kassym-Jomart Tokayev has shown little sign of any willingness to pursue more relaxed domestic policies despite the increasing calls for more democratic participation, mainly from young urbanites in Almaty.

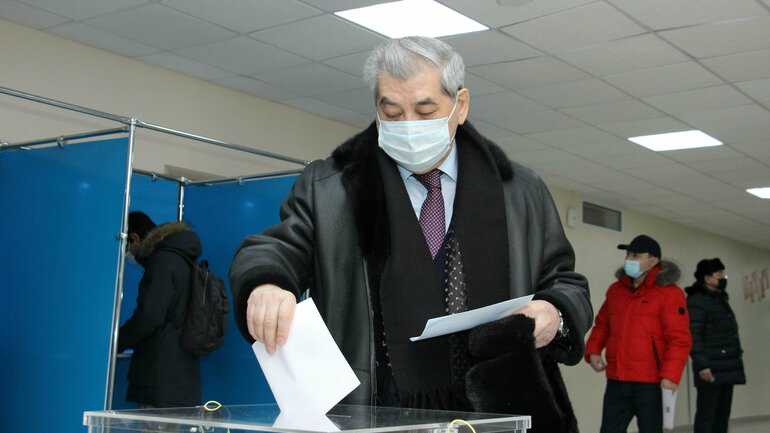

The elections to the lower House of Parliament, on 10 January appeared, on the face of it, to offer voters a genuine choice: there were 312 candidates from five different parties standing for election to 98 seats. However, the political system is dominated by Nur Otan, the President’s party which has won landslide victories in all parliamentary and presidential elections since it was founded in 1999. The other parties that fielded candidates also have close ties to the government and therefore do not offer a genuine political alternative. The only state-registered party that is even vaguely critical of the government, the OSDP, opted to boycott the elections, even though it was eligible to stand. Without a genuine opposition, the public’s interest in the election campaign was muted. Even so, national leaders’ nervousness was apparent: in the run-up to the elections, known political activists were arrested and strict legal curbs were imposed on local independent election monitoring.

Despite these precautions, election day saw protests taking place in several cities, mainly Almaty. Around 100 demonstrators were temporarily detained, and independent election observers were denied access to polling stations. What’s more, the “against all” option customarily available in Central Asia was missing from ballot papers. Independent experts say that this would have enabled voters’ protests to be quantified in numerical terms. Numerous social media posts show that instead, many voters opted to spoil and hence void their ballots by crossing out candidates’ names or writing down alternatives as an expression of protest.

The provisional official election result is sure to be to the government’s liking: as always, Nur Otan has a healthy lead with 71.9 per cent of the votes, followed by Ak Zhol (10.95 per cent) and Narodnaya Partiya Kazakhstana (9.1 per cent). The other two parties (Auyl und Adal) failed to clear Kazakhstan’s 7 per cent hurdle and will not hold any seats in the new Parliament. Turnout is reported as 63.3 per cent nationwide. However, in Almaty, the country’s largest city, less than a third of voters went to the polls, a continuation of a trend seen in previous elections, but also a clear expression of – futile – protest.

From the regime’s perspective, all previous elections in Kazakhstan passed off in a peaceful and orderly manner, although OSCE observers described them as neither free nor fair. This time round, even more pressure and influence were brought to bear by the government than during the presidential elections in 2019, even though the lack of any political alternative meant that it had no need to be concerned about genuine change. However, it is clear that increasing numbers of young urbanites in Kazakhstan are no longer satisfied with the situation.

No surprises in Kyrgyzstan

By contrast, Kyrgyzstan is regarded by its Central Asian neighbours as a hotbed of anarchy and threat – in part because on three occasions since the country gained its independence 30 years ago, a president has been ousted from office by the power of protest. Due to its active civil society and more open atmosphere, at least in comparison with its neighbours, Western politicians still describe Kyrgyzstan as a liberal and even democratic country.

The elections on 10 January took place after vigorous protests were sparked by the obviously rigged results of the regular parliamentary elections in early October 2020, prompting not only the annulment of the election but ultimately also the resignation of President Sooronbai Jeenbekov, in office since 2017. Sadyr Japarov emerged as the country’s new strongman leader. A populist previously – and lawfully – convicted of hostage-taking, Japarov was freed from prison by his supporters during the unrest and then used the general chaos to secure both the premiership and the presidency for himself 10 days later. Japarov continued to use the situation adroitly for his own purposes, not least by postponing the parliamentary elections, whose date had been already determined, until summer and setting a date for presidential elections first. He then promptly resigned – the constitution would not have allowed him to stand otherwise – although not before placing his closest allies in key positions, and embarked on a grand tour of the country in order to make lavish promises to prospective voters. As expected, he was elected with over 80 per cent of the vote, a remarkable outcome by Kyrgyzstan’s standards. Not one of the other 17 candidates could be regarded as a genuinely convincing opponent.

It thus seems very likely that a populist who is well-connected to the criminal underworld and whose supporters do not shy away from robust action will become the sixth president of the Kyrgyz Republic. He has promised his voters a golden future. And his new powers will help him here: in a referendum, conducted concurrently, on the country’s future governance, 83.3 per cent voted for a reversion to a presidential system, with work on a new constitution continuing over the next two months.

The OSCE’s limited election observation mission (LEOM) has reported a number of irregularities. However, the critical flaw in Japarov’s election victory and in the outcome of the referendum is voter turnout, which was below 40 per cent. This cannot be explained solely by a change in electoral law which meant that voters could only cast their vote at their place of residence. It is more likely that a growing number of disillusioned voters are simply turning their backs on politics.

What does the future hold?

Election day brought no surprises, then, and offers little hope for a democratisation process in the two countries. In Kazakhstan, no reform momentum can be expected from the new parliament, while in Kyrgyzstan, there is a risk of strongman rule. Despite all the differences between the two countries’ political conditions, a worrying trend can be observed in both: a growing share of the population understands that the elections are not about them and their interests, but are simply a mechanism for the elites to legitimise their power and interests. As a consequence, these voters are turning away from politics. It is noticeable that in Kyrgyzstan, this vacuum is being exploited by minorities that are willing to use violence. There is also a growing urban/rural and generational divide in both countries, which could well play into the hands of the elite. In consequence, events such as those seen in Belarus, where the mobilisation of large swathes of society can be observed, seem even less likely in Central Asia than before.

Beate Eschment is a researcher at ZOiS.