Societal Fragmentation in Belarus

A little more than a year since the 2020 Belarusian presidential election triggered antigovernment protests, the balance sheet of what the protesters have achieved is sobering. Belarusian and Russian media refer to their success in preventing another colour revolution, and Belarusian politicians take pride in having strengthened Belarusian and Russian statehood. The mobilisation, meanwhile, has clearly not achieved its immediate goals: president Aliaksandr Lukashenka remains the central figure in Belarus’s political system. He has extended his control over the country’s elite and society while accepting increased dependence on Russia.

Even if political change now seems unlikely, studies of authoritarian systems should go beyond a focus on the political elite. Rather, it is important to appreciate the profound societal changes that accompany moments of rupture, even those that lead to institutional continuity. With that aim, ZOiS conducted an online survey in June 2021 among 2,000 Belarusians aged 16–64 living in places with more than 20,000 inhabitants. Quota sampling reflected the underlying population structure in terms of gender, age, and place of residence. The survey was unique in that it included largely the same people who were interviewed during a first round in December 2020.

Persistent societal fragmentation

In February 2021, a ZOiS Spotlight article revealed the overall attitudes of Belarusian society towards the country’s political setting, with survey respondents categorised as strong or moderate regime supporters, undecided, or strong or moderate regime critics.[1] Between December 2020 and June 2021, there was no significant shift in the overall numbers of people in each category (figure 1). Roughly half of those surveyed were regime critics, a share that decreased slightly between the two surveys, whereas the proportion of undecideds grew. About one-third of respondents continued to support the regime.

Figure 1: Belarusians’ attitudes towards the regime, December 2020 and June 2021

Respondents’ positions reflected their attitudes towards the regime’s institutions and symbols, voting choice and participation in protests, views on the postelection protests, and broader political attitudes. From December 2020 to June 2021, the share of respondents who did not trust the president at all declined from 45 per cent to 41 per cent, whereas the proportion of those who did not know how to answer this question increased. Belarusians’ views since the presidential election represent a profound shift compared with public opinion before 2020, when Lukashenka enjoyed significant personal approval, bolstered by a combination of repression, co-optation, and a certain legitimacy.

A finding that echoes previous research is the relevance of gender in attitudes towards the regime. In June 2021, 15.5 per cent of women expressed strong support for the government, compared with 11.2 per cent of men. Female respondents were also significantly less likely to strongly criticise the regime.

Another pertinent factor is age. Young people have been vocal in their opposition to the regime, and those who protested have suffered its violence in disproportionate ways. Young people have been active on social media, where mockery of the president has been frequent. A closer analysis confirms that strong regime support correlates very closely with older age, a link that further increased from December 2020 to June 2021, as older people tended to become more supportive of the regime.

At the same time, criticism of the regime does not relate systematically to age. If anything, older respondents were also more likely to be strong critics of the regime. Older Belarusians therefore hold diametrically opposite views: relative to the rest of the population, they are both more supportive and more critical of the government.

In addition, Lukashenka’s base continues to consist of those who live in smaller settlements, identify as Orthodox, have lower levels of education but higher disposable incomes, and, irrespective of income, are employed in the state sector. These basic indicators are of great significance and indicate how fragmented Belarusian society has become. People with diverging views on current politics can live to a large extent in different worlds.

What should Belarus’s priorities be?

Asked about their preferred way out of the current impasse, a clear majority of respondents said they would like to see new elections. This was the view of 43 per cent in December 2020 and of 53 per cent in June 2021. Constitutional reform continued to rank highly on respondents’ wish lists; this process is under way but will in all likelihood further secure the president’s power.

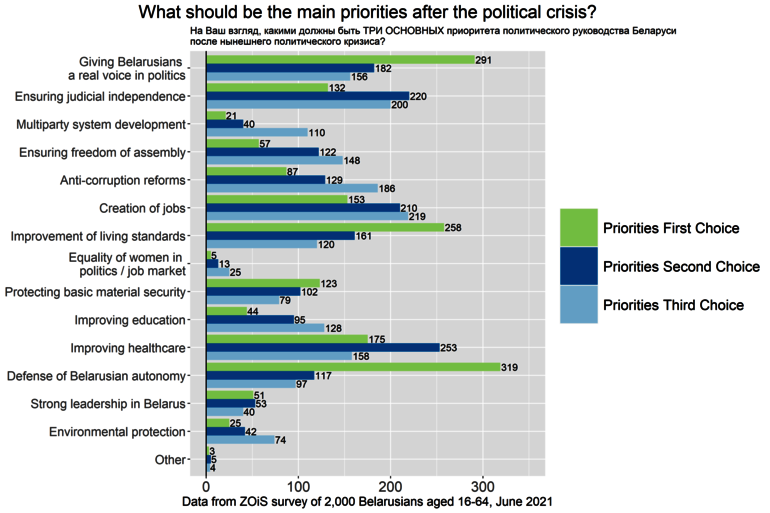

Looking to the future, respondents identified three sets of priorities for Belarus (figure 2). The first set revolved around political participation. Belarusians frequently cited genuine involvement in the political process as the first priority for their country and judicial independence as a second priority. Meanwhile, issues relating to protests or the development of the party system were much less prominent.

The second set of priorities consisted of economic topics. Job creation and the improvement of living standards were clearly the most pressing issues, followed by improvement of the healthcare system.

The third set concerned Belarusian autonomy, which respondents continued to mention most often as their first priority—even more so in June 2021 than in December 2020. In light of the increasingly close integration of the Belarusian and Russian economies, a feared trade-off of Minsk’s sovereignty for the Kremlin’s backing could further increase Belarusians’ frustration with their country’s leader.

Figure 2: Belarusians’ views on the priorities for Belarus, December 2020 and June 2021

A gulf separates large swathes of Belarusian society and the political elite, as the economic and political climate is increasingly tense. Financial concerns are omnipresent, with 80 per cent of respondents worried about the state of their personal finances over the next six months. At the same time, the regime continues to tighten its control over society and limit political activism. In early October 2021, the Belarusian authorities opened a criminal case against opposition leaders Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya and Pavel Latushka for their ‘unauthorised appropriation of power’. Such measures are likely to limit how people get involved politically, but the gap between society and the elite will only grow if the Belarusian regime ignores the worries and expectations of ordinary Belarusians.

[1] Please note the slight difference for the December 2020 data as presented here. This is due to one question not being asked in the June survey, it was substituted by a different question for comparability and identification of the development over time.

The first survey in December 2020, referred to here as a comparative reference point, was funded by the German Federal Foreign Office. The second survey in June 2021 was funded by ZOiS.

Félix Krawatzek is a senior researcher and head of the 'Youth in Eastern Europe' research cluster at ZOiS.