Romanian Protests

In late January and early February 2017 Romania witnessed the largest popular protest in its history as hundreds of thousands took to the streets for several consecutive days to protest against a government ordinance (OUG 13) that would have decriminalized certain types of corruption. While the most striking images came from the protests in Bucharest, where up to 300,000 braved the freezing temperatures on 5 February, large and mostly peaceful protests also took place in many other cities (and even smaller towns). Protests were larger in traditional opposition strongholds like Bucharest, Cluj, Timisoara or Sibiu, but thousands of protesters turned out throughout the country. Taken aback by the strength of the reaction, the government withdrew the ordinance, and Florin Iordache, the Justice Minister responsible for the ordinance, announced his resignation. While the protests were widely seen as a rare piece of good news in an era of liberal retrenchment, their implications for Romanian democracy and rule of law are more complicated. The protests may simply have slowed down rather than stopped the government’s efforts to amend the Penal Code. These amendments are at the top of the agenda for several political leaders and particularly for Liviu Dragnea, the leader of the main governing party (PSD), who has already received a suspended prison sentence for electoral fraud and faces another trial on corruption charges.

More broadly, the protesters failed to achieve their more maximalist demands of forcing the resignation of the Prime Minister Sorin Grindeanu and the PSD-leader Liviu Dragnea. Since the protests failed to trigger significant defections from the governing parties, the government continues to enjoy a clear parliamentary majority, Romania is faced with a difficult and potentially destabilizing dilemma about the sources of democratic legitimacy. On the one hand, the ex-communist PSD won a clear victory in the December 2016 parliamentary elections, where it obtained more than double the vote share of the largest opposition party (44 percent vs. 19 percent in the Chamber of Deputies.) The PSD leadership has invoked this recent victory as a democratic mandate for its legislative agenda. While one may question the strength of this mandate due to the low electoral turnout (under 40 percent), it is nevertheless clear that currently the parliamentary opposition does not offer a real political alternative.

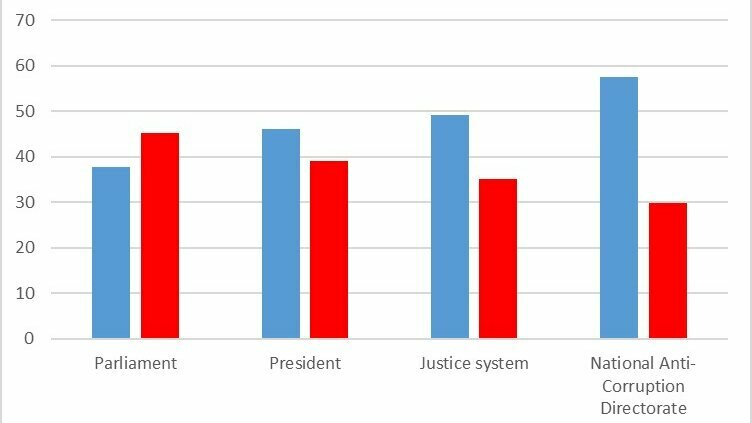

On the other hand, a significant challenge to the PSD democratic mandate comes from President Klaus Iohannis, who in the second round of the November 2014 presidential elections received almost double the number of votes that the PSD won in December 2016 (6.3 million vs. 3.2 million). Given that Iohannis strongly criticized the government ordinance and even joined the anti-corruption protests in Bucharest on January 22, this tension could have triggered a full-blown constitutional crisis with Dragnea threatening to suspend Iohannis for over-stepping his constitutional mandate. The PSD’s quest to use its electoral mandate to modify the Penal Code is further complicated by the fact that – though unelected – both the justice system and the National Anti-Corruption Directorate (DNA) enjoy noticeably higher popular trust than the parliament according to a nationally representative survey [1] fielded from mid-December 2016 until mid-February 2017 (see Figure below). Last but not least, the large number of citizens willing to spend hours protesting in the bitter cold, combined with the much smaller scale of attempted pro-government protests, arguably created an alternative source of democratic legitimacy.

Note: Data are based on a series of trust questions (scored 0-10) from a post-electoral survey (RES 2016). Answers from 0-4 are coded as distrust, while 6-10 is coded as denoting trust.

But how far does the new government’s legitimacy extend? This issue was raised directly by President Iohannis, who argued that the PSD’s electoral campaign – and hence its mandate – was based on economic issues and not on reversing anti-corruption efforts and therefore initiated steps to call a referendum on the Penal Code changes. This distinction is borne out by data from the same post-electoral survey: while respondents who identified the economy (including jobs) as the country’s most serious problem were significantly more likely to see the PSD as the party best suited to tackling the problem (and, hence, were more likely to have voted for the PSD), those primarily concerned with corruption were much less enthusiastic about the PSD, and were more likely to endorse the Union Save Romania (USR), a political newcomer that ran on an anti-corruption/anti-establishment platform. While in the overall population economic concerns outweighed corruption worries (36 percent to 24 percent), and therefore arguably contributed to the PSD’s electoral success, for educated, young-to-middle-aged Romanians the two concerns were evenly balanced (around 30 percent). The PSD’s heavy-handed and hurried approach to amending the Penal Code mobilized this fairly substantial anti-corruption constituency, and thus triggered the massive protests of January/February 2017.

These patterns are confirmed by results from a separate online survey of protest participants. Even though corruption provided a clearer focal point than in other recent cases of large-scale popular mobilization, the Romanian protesters nevertheless varied significantly in the extent to which they embraced the different protest objectives. Over 80 percent of the respondents expressed their opposition to the emergency ordinance and roughly two thirds highlighted the fight against corruption and for the rule of law, but only about one third claimed that they protested against the government or the main ruling party, and even fewer (6 percent) wanted to express their support for the opposition. This heterogeneity helps to explain why the protests abated fairly quickly after the government withdrew OUG13 and why the protests did not succeed in bringing down the government, even though Romania had a precedent of the much smaller protest wave of November 2015 having brought down the government of Victor Ponta.

Overall, the 2017 Romanian protests confirm that like elsewhere in the region, the relative passivity and patience of the first two decades of the post-communist transition, which had already been undermined by the hardship of the Great Recession, has definitely given way to greater popular mobilization. However, while such mobilizational episodes represent an important short-term counterweight against the dangers of delegative democracy (or worse), they cannot effectively substitute for a robust parliamentary opposition and a functioning system of institutional checks and balances, both of which are unfortunately in short supply in Romania and much of the rest of Central and Eastern Europe.

[1] Romanian Elections Study (RES), 2016 Parliamentary Elections (financed by CNCS-UEFISCDI, grant PN-II-ID-PCE-2011-3-0669).

Grigore Pop-Eleches is Professor of Politics and Public and International Affairs at Woodrow Wilson School, Princeton University.